Erasing Shadows

by Daniel Bird

There are more important things than film. Nevertheless, film plays a role in things more important than itself, like nation building. Film plays a part in the process of reforging national and ethnic identities in the post-Soviet borderlands: Central Asia, Transcaucasia, the Baltics, Belarus and Ukraine.

Yet there is a tendency amongst film writers, programmers and distributors to treat the cinemas of the former Soviet Union as if they still belonged to a singular, amorphous bloc — a tendency best illustrated by the reliance on convenient but unhelpful descriptions, like “Russian language cinema.” In July of last year, Putin published an essay, ‘On the Historical Unity of the Russians and Ukrainians.’ When we describe Soviet-era films from countries other than Russia as Russian language film, we are, perhaps without knowing it, complicit in the reinforcement of Putin’s empire fantasy. (This, of course, is besides the fact that these films were not always in Russian.)

Film agencies and archives from these regions face several challenges, practical and financial, the most pressing of which being that whilst Russia has relinquished the ownership rights to films from the post-Soviet borderlands, they have kept hold of the original camera negatives. In this digital age, this presents difficulties for film agencies from these regions to restore, screen and distribute their own films.

It is time we started thinking about heritage cinema from former Soviet countries for what it is: a post-colonial problem.

Take, for example, The Ascent. The film is in Russian, the export rights are handled by Moscow-based Mosfilm. And yet, its director, Larisa Shepitko, was Ukrainian, and the author of the novella upon which the film was based (‘Sotnikov’) was Belarusian (Vasil Bykaŭ).

Of course, we must be wary of shoehorning this film into, for example, Belarusian or, even more tenuous, Ukrainian film history. Nevertheless, we should not ignore the interplay between nations under the Soviet Empire and the Russian Empire before that, especially as the involvement of individuals behind the making of such films reveals yet more nuances of allegiance.

Along with Ales Adamovich, Bykaŭ established the Belarusian PEN club – perhaps the only one of its kind to be recognised as an enemy of the state. Both used their weight to rally against the Soviet mishandling of the Chernobyl disaster, and in the final decade of his life, Bykaŭ was the intellectual thorn in the side of Belarus president Lukashenko. Larisa Shepitko elevated Bykaŭ’s source novella into a parable about the importance of being uncompromising – an aspiration for some, a necessity for others.

We could also look at an example from the post-Soviet period – Maria Saakyan’s The Lighthouse. To all intents and purposes, the film is an independent Russian production, in Russian. Yet it is based on a screenplay by a Georgian screenwriter, drawing on the Georgian–Ossetian War, directed by an Armenian, in Armenia, transposing the drama to the first Nagorno-Karabakh War.

There is, of course, a paradox. On the one hand, the way we write about heritage film, programme it and distribute it, can be used as a means of reclaiming a sense of national identity. It can bring audiences together, both at home and abroad, and can even play a part in contemporary politics. On the other hand, we must be wary of the danger of using heritage film to create artificial, singular, and, above all else, imagined communities, as a means of reifying national and/or ethnic boundaries at the expense of broader political communities — something which both Putin’s empire building and certain Ukrainian far right movements like Svoboda are trying to do.

***

In September 2015, in Kyiv, a screening of Sergei Parajanov’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors was organised to celebrate the film’s fiftieth anniversary. Parajanov was, of course, an ethnic Armenian, born in Tbilisi, Georgia, who studied in Moscow and was, for the most part of his working life, employed by Dovzhenko Studio in Kyiv. Nevertheless, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is of particular significance not just for film history, but for Ukrainian culture as a whole — it was even the name of what was to be Ukraine’s song in Eurovision 2022. The screening in Kyiv was introduced by the then Ukrainian president, Petro Poroshenko.

The irony of presenting a film by Parajanov, a symbol of suffering at the hands of Soviet authorities, barely a year after the Russian annexation of Crimea and the outbreak of fighting in the Donbass region, was not lost on Poroshenko, and the screening was a major event. It was covered by television and attended by luminaries of Ukrainian cinema past, as well as the leading lights of the present, like Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy, director of The Tribe, which had been released to international acclaim just the previous year.

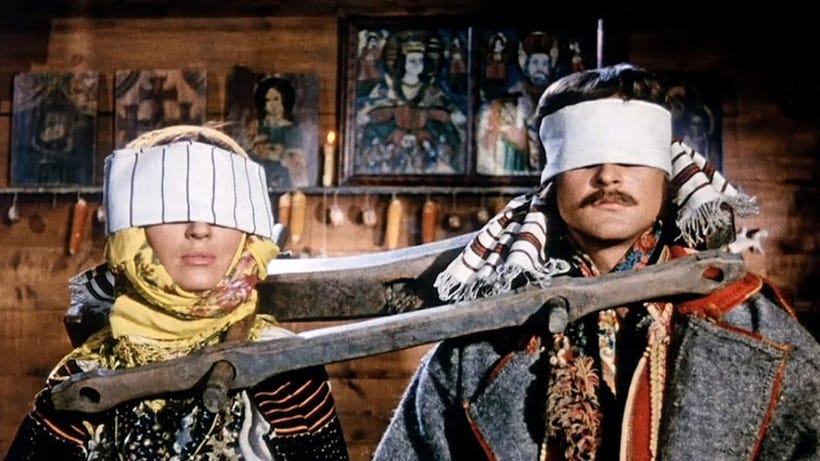

The language of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is not Russian, but Ukrainian. What is more, it is in the Hutsul dialect. The film was commissioned in 1964 to mark the centenary of the birth of the Ukrainian author, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, and like Kotsiubynsky’s book, Parajanov’s film mines Hutsul folklore.

The Hutsuls are an ethnic subgroup in Western Ukraine in the Carpathians along the border with Romania. Since the Union of Brest in 1596, Ukraine has had, in addition to the Orthodox Church, the Greek Catholic Church — one looks to Moscow, the other looks to Rome.

All these details are significant, because they are weapons in the battle to determine not just what Ukraine was in 1965, but also what it was in 2015.

Nationalists found mostly in Western Ukraine have credited the Greek Catholic Church as safeguarding their identity, first under the Poles, then the Hapsburgs, then the Poles again and, finally, the Soviets. Alternatively, some Ukrainian nationalists look beyond the Union of Brest, beyond Christianisation in 988, to a mythical, primordial and neo-pagan past. Parajanov tapped into this.

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors revelled in the ethnic, the folkloric, and the poetic. It influenced similar films throughout Transcaucasia and Central Asia. To give just two examples from Georgia and Uzbekistan: Tengiz Abuladze’s The Plea, (1967, based on the poems of Vazha-Pshavela) and Ali Khamraev’s Man Follows Birds (1975).

James Steffen, the leading scholar on Parajanov, has noted how the filmmaker’s status as the leading director of the “poetic” school of Ukrainian cinema was associated with “bourgeois nationalism.” In Ukraine however, it inspired a subset, the Kyiv School of filmmakers, central to which was Yuri Illienko who had been the cinematographer on Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors. Himself a student of Sergei Urusevsky, the virtuoso cinematographer behind three remarkable films by Mikhail Kalatozov (The Cranes are Flying, The Unsent Letter and I am Cuba), one of Illienko’s most dazzling films is the widescreen, psychedelic The Night of Ivan Kupala:

Based on Gogol, it reclaims his literary roots in Ukrainian folklore.

Immediately after Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, Illienko made his remarkable directorial debut, A Well for The Thirsty:

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors had been produced at the very end of Khrushchev’s tenure, but A Well for The Thirsty sat on the shelf until well into Perestroika and marked Illienko’s first brush with state censorship. The thaw had stopped.

Despite proceeding to camera tests, Parajanov’s subsequent project, Kyiv Frescoes, never made it into production. Effectively blacklisted in Ukraine, Parajanov was offered work by Armenia’s Armenfilm, who were eager for their own Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.

When the literary screenplay was submitted for approval by Goskino in Moscow, the critic Mikhail Bleiman protested about the poetic (as opposed to realistic) tendency in Parajanov’s filmmaking. Fortunately, The Colour of Pomegranates (or Sayat Nova as it was then known) went into production, although that too experienced interference from Moscow, limited distribution and, during Parajanov’s imprisonment, banning.

The Colour of Pomegranates along with the two films Parajanov made during the 1980s (The Legend of the Surami Fortress and Ashik Kerib) are sometimes referred to as a trilogy celebrating Transcaucasia. There are, however, traps we must be wary of.

These films are not exclusively concerned with the respective cultures of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. Rather, in them Parajanov presented an inclusive vision of a mountainous range along the Silk Road, where goods, peoples, languages and cultures mixed.

Moreover, these films were not ethnographic documents, and Parajanov was very open about creating his own rituals for his film. In Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, it was Parajanov who devised the ancient wedding ritual involving a yoke. His creation was so effective that some Hutsuls reportedly adopted it as ‘authentic.’ Conversely however, Parajanov’s ritual ‘innovations’ in The Colour of Pomegranates and Ashik Kerib sometimes caused religious offence.

This makes for an interesting contrast with Soviet attempts during the 1930s to fuse nationalism and socialism, where for example, ‘new’ folk dances were derived from ‘native’ dances because of the revolution. More importantly, these reactions illustrate not so much the shadows of forgotten ancestors, but rather the desire for them, both under Soviet occupation and during the post-Soviet era, when the nation was rediscovering itself.

***

Throughout the Soviet period, Illienko dreamed of a film about Hetman Ivan Mazepa, who turned against Russian Tsar Peter the Great to fight alongside King Charles of Sweden at the Battle of Poltava in 1709. Today, Poltava is in eastern Ukraine, not too far from Luhansk and Donetsk. The character of Mazepa exerted a profound influence on the Romantic movement, inspiring works in literature and music by the likes of Byron, Pushkin, Slowacki, Hugo, Tchiakovsky and Liszt. However, during the Soviet period, Mazepa was synonymous with Ukrainian nationalism.

Ten years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Illienko got to make his dream project, A Prayer for Hetman Ivan Mazepa. The film cost 2.5 million dollars, which, twenty years ago, was an unheard-of amount for a Ukrainian film. The project was supported by Ukraine’s then Prime Minister, Victor Yushchenko, and Mazepa was played by Bohdan Stupka, an actor made famous in Illienko’s White Bird with the Black Mark who was also Ukraine’s Minister of Culture at the time.

The film opened out of competition at the 2002 Berlinale, where it was deemed at best incomprehensible, at worst an embarrassment. It opens with Peter the Great sexually assaulting someone on top of Mazepa’s coffin:

Rape figures throughout the film: rape as metaphor, rape as part of the plot, and rape as gratuitous spectacle. It would be convenient to dismiss Illienko’s film as deranged, camp hysteria — if not for the fact that Peter the Great is Putin’s hero. Following his invasion of Ukraine, Putin used a rape joke to explain his political goals to French president Emmanuel Macron: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/feb/26/valdimir-putin-russia-ukraine-inside-his-head

***

Parajanov died in 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall but before the dissolution of the Soviet Union. After he died, both his legacy and legend were assimilated by Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine. Illienko made both a documentary about Parajanov, and a film based on Parajanov’s own recollections of life in the Dnipropetrovsk labour camp. While Parajanov’s films were deemed repositories of indigenous cultures, his myth became a symbol of defiance against Soviet oppression; both served as tools in the creation of three lots of national identities. Parajanov had become a means to an end.

The irony of many Eastern European filmmakers whose careers spanned both the communist and immediate post-communist periods is how those oppressed under one regime become part of the establishment the next. My enemies’ enemy, after all, is my friend.

However, in Illienko’s case, both he and his two sons were drawn to the extreme far-right Svoboda party. He died in 2010, but not before remixing the sound of A Prayer for Hetman Ivan Mazepa, re-editing it and adding a voice over that both explained the action and commented on the production.

***

Just over sixty years ago, on the other side of the Carpathians, a Polish war film was being filmed, although it looked like a Western. Ogniomistrz Kaleń (Artillery Sergeant Kalen) was based on a book by Jan Gerhard, titled ‘Łuny w Bieszczadach’ (Glow in the Bieszczady Mountains), and both film and book tell the story of a Polish soldier fighting against the Ukrainian Insurrection Army (UPA) during the Second World War. At the heart of UPA was Stepan Bandera, a Ukrainian ultranationalist who fought alongside the Nazis against the Red Army, the Polish communists and the Polish underground. After the War, he settled in West Germany where, in 1959, he was assassinated by the KGB in Munich.

Just over fifty years later, the outgoing Ukrainian president, Yushchenko, attempted in 2010 to bestow an award upon Bandera as a national hero. This was deplored not just by pro-Russian factions, such as former Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, but also by Polish and Jewish groups. While Bandera never received his posthumous award, during the 2014 Euromaidan protests, his portrait was once again invoked by a tiny minority faction as a symbol of Ukrainian independence. It is this association forged by Putin between the notion of an independent Ukraine and Bandera’s fascism that provides a rationale for invasion.

Culture is a battleground. An early casualty in Russia's invasion of Ukraine was the destruction of the Mariya Primachenko museum, dedicated to a folkloristic artist working in the naive style. There has been a lot of talk these last few weeks about Russia's invasion as not just a "war," but genocide in the legal sense as defined under international law. In addition to extermination of Ukrainian political leadership, Putin's agenda includes the destruction of signifiers of Ukrainian culture as something distinct from his concept of Russian. We can, therefore, assume that Ukrainian films are under threat, too.

It would be nice to think that, one day, we will be able to write about, programme and distribute film in a post-nationalist era, where histories and identities are superseded by understandings of cultural difference based on an inclusive vision of political community. This is not what Putin is offering.

Until we reach that point, we must be both aware and sensitive to nationalities, languages and ethnicities in the post-Soviet Borderlands, as well as how they have been shaped by both politics and history.