I saw the film On the Waterfront and my main takeaway was ‘f**k, Karl Malden is stealing the show as the priest’. It’s crazy that the main takeaway for most people is Brando, because Malden is a tour de force. Then I saw One-Eyed Jacks and again, I was more blown away by Malden’s performance than the lead guy Brando. I guess my question is, are there classic films that live up to their reputation but in a whole different way than you expect?

Thank you for sending in this question, which I am keen to get to just as soon as I have lightly chided you for the act of self-censorship in your first sentence. There was really no need, my friend; no need at all to asterisk out a bad, naughty word, certainly not on my behalf, nor — unless I’m much mistaken — to get past any kind of barrier set up by my dear hosts at Animus dot com! This leads me to worry (and I hope you appreciate my heartfelt concern for you) that these times have led you to auto-redact your own writing as a general kind of house style, which is a particular shame in this instance because it is a thought of yours that has been so ill-served. Surely you didn’t think ‘f**k’? You must — must! — have thought ‘fuck’. Perhaps you even said ‘fuck’, to someone else or your own damn self, and good for you if so! It means that cinema traversed your being, that Karl Malden got you bad. Out with it!

Now, on to this question, which I have enjoyed chewing over for the last day or so. I think there are two discrete thoughts going on in it, however, and would like to address both parts. In the beginning you mention Karl Malden giving a tour de force in On the Waterfront (1954) and again in One-Eyed Jacks (1961) (the latter of which I haven’t seen); this leads you to a question, which you preface with “I guess”, perhaps because it isn’t a wholly obvious question stemming from your set-up. Let me see if I can drum something up for both bits.

When I think of Karl Malden I think particularly of a big man: I associate him primarily with A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), in which his character, Mitch, is written as being big; in a key scene, he tells Blanche his height and weight and lifts her up, finding her to be light as a feather. Malden himself was tall and thick-set, and possessed of such a schnoz, my gosh, what a schnoz! Let me quote Ronald Bergan’s whole paragraph on it, from his heavenly Guardian obituary of Malden in 2009:

Like W.C. Fields and Jimmy Durante, Malden had one of the most celebrated non-Roman noses in cinema. But whereas those of the two former entertainers produced a comic effect — Fields's bibulous one looked as if it were stuck on like a clown's, and Durante's schnozzle was like a carnival mask — Malden's proboscis seemed to add dramatic intensity to his performances. The more impassioned he became, the more the nose seemed to go on red alert.

Isn’t that great? The bigness of Malden is important, because it is used very well to offset Vivien Leigh but also Marlon Brando, a wiry and feline short king; the same can be said of his, how can I put this, non-hotness. It’s so crucial in these films to have an everyman, for many reasons — one being to throw the sexy young movie stars into relief, another being to ground the film itself, and a third being to surprise you by revealing layers to the everyman himself: vulnerability, cruelty, whatever it may be. Malden could do all that, and I think he laid the groundwork for other actors, of the 60s and 70s. How not to think of Gene Hackman, for instance, when you see Malden’s good, bright face?

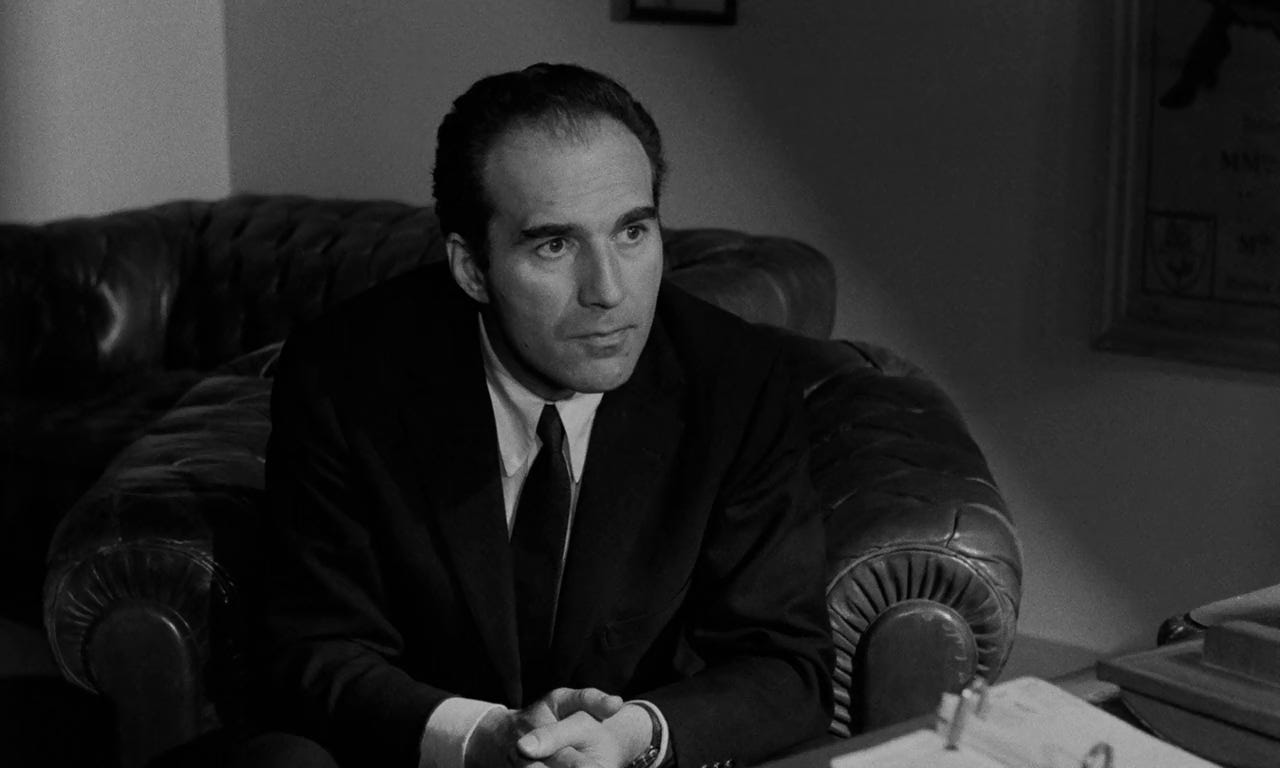

That sense of bigness and a kind of deceptive ordinariness being used to counterbalance a young tiger made me think of Le Doulos (1962) by Jean-Pierre Melville, in which Michel Piccoli quite brilliantly makes the most of a supporting role opposite a young, raffish Jean-Paul Belmondo. Piccoli’s character is a crappy, conniving businessman, who comes up against Belmondo’s principled crim in a crucial scene — and what he does at this point is to offer up complete normality, a recognisably fallible human; a bloke, for god’s sake, smoking a cigarette and admitting defeat. It’s in part this imbalance between, on the one hand, an actor, and on the other, a movie star, that gives the film its verve. Belmondo is a good actor — I like him very much in Léon Morin, Priest (1961), again by Melville, in which he keeps his charisma at a low simmer — but he operates in a different mode, and rightly so. Piccoli was never a movie star, even though he was on several occasions a leading man: in films from Le Mépris (1963) to Belle de Jour (1967), his open face and rumpled affect again offset a magnetic young premier; the buttery mashed potatoes to their truffle shavings, if you will.

I think this is also the function that Philip Seymour Hoffman performs in The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), opposite a duo of golden movie stars (plus Gwyneth Paltrow). Hoffman wasn’t hulking exactly — in fact, he seemed somehow able to make himself any shape you like — but was often used most felicitously as one of cinema’s big guys, and he was very much an everyman in his lack of vanity, in the way he could touch the abject. In Ripley his Freddie is a preening, smarmy, affected, waspish party boy — and he offers something real for Jude Law and Matt Damon to play with and against, respectively. Who can forget his drawl, “How’s the peeping, Tom?”: he isn’t fooled by Ripley, but understands his peripheral status and his hunger. The difference is that he could never hope to seduce, or to move across boundaries like Tom. This contrast in their demeanours is necessary to the film. On the one hand, an actor; on the other, a movie star. It’s a simple question of chemistry — but it’s something that the movies forget all too often now, with our lack of character actors and surfeit of hot young premiers. There’s only so much Jesse Plemons can do!

Now (perhaps more briefly) to the second part of your question, about films living up to their reputation in unexpected ways. I’m tempted to give a slightly cop-out answer and say that this is the case of almost all classic films, because the freshness and brilliance of a real masterpiece will always surprise you on first watch, will so often make a mockery of your preconceptions. That was the case for me when I watched The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) for the first time, for instance: how could I have expected anything like the fire, the modernity, the extraordinary performance piece, the questing intelligence that I witnessed, open-mouthed like an idiot? The sheer starkness of the film, and its disorienting camera angles, feel like the work of somebody perfecting cinema, making it new and vital before your eyes. It’s always the case with The Apartment (1960), whose sharp aftertaste dims in the memory between viewings, only to surface again with a vengeance upon rewatching: how unsparing Billy Wilder is, how smart his film-writing, and how fine and free the acting from Lemmon and MacLaine. It has the feeling of breathing in after brushing your teeth.

But I do know what you mean — that some element in a film can be so unexpected, and wrongfoot you, or pull you in. Two films spring to mind, and one of them I’m afraid is Love Actually (2003). Much has been written and said about Emma Thompson’s exquisite performance in a film that doesn’t deserve her; in a film, in fact, which scorns her and constantly puts on display a crass, ball-scratching view of women. I would rather sell my children to a stranger for eighty quid in a street market than watch Love Actually again, of course, but I can never forget Emma Thompson crying, looking beautiful in her offensively terrible haircut, crap earrings and teacher-length midi skirt, those boorishly conceived signifiers of a boring perimenopausal mum-wife that you’re just dying to cheat on, aren’t you. What makes it so lacerating is that she cries while standing up; that she palms away her tears; that she then arranges a cover on the bed, thoughtlessly, just so as to do something. You can see her thoughts travelling so quickly, everything falling around her; and this moment represents so much more: it’s a fight for ambiguity in a sea of facility, a struggle against lies and oafishness.

One more film: Dog Day Afternoon (1975), which I think has been greatly harmed by Al Pacino’s reputation, or by our false perception of what Pacino means, what “method” means. When I saw the film for the first time, I simply could not believe what I was seeing: what I had imagined as a Hollywood hold-up kind of thing, with the obligatory tense stand-off, and heroics, and perhaps a moral at the end, was in fact an eccentric, beautiful character study, with a wholly unexpected performance by Pacino, working the upper registers of his voice and giving his heart and soul to the story of a real outsider. It’s queer and impassioned and beautiful and funny; there is an unfussiness at play, and — as with many old films, which you expect to be somewhat dusty — feels bracingly modern. It never talks down to its audience, assuming of us, as few American films now do, that we will play our part and put some effort in.

Those are a couple that spring to mind, but I could go on forever! Godard’s 60s films, at any rate, all challenge his reputation as a turgid Marxist; or try Youssef Chahine’s Cairo Station (1958) for an astonishingly vivid depiction of grim desperation, touching on class and violence and sexuality in ways that are quite startling. OK, I’m going to stop there. One more: Bunny Lake is Missing (1965) is so weird and upsetting! No, really, that has to be the end. Fuck!

Send your questions anonymously to Caspar at this link, no personal information is collected.